Interview: COLUMNAE’s Jovan Vesić

Developed by Moonburnt, a Belgrade-based three person studio, COLUMNAE: A Past Under Construction guides players through a nonlinear journey in a post-apocalyptic steampunk world. With the game consisting of eight chapters and a demo already available, I chatted with multitalented developer Jovan Vesić on the project and his artistic sensibilities.

Erik Meyer: The game drops players into a steampunk point-and-click adventure amidst a factory closing and a worker protest. As Columnae relies a great deal on dialogue and character interactions, speak to the kinds of interactions you enjoy exploring as developers. What is it about both social and object puzzles that people find so intriguing?

Jovan Vesić: Object puzzles are the mainstay of the old-school adventure games that we based our gameplay on from the very beginning. But during the earliest stages of development, COLUMNAE was meant to be a game without any dialogue (or even without any words at all), gameplay-wise similar to Machinarium. As the story and the world surrounding it kept growing and becoming more complex, we soon realized it would be impossible for us to tell our stories without having a strong verbal component, and later, as the political aspect of the story became more dominant, the dialogues grew even more intricate in an attempt to better convey the complexity of the social situations at hand.

Of course, we could have still just left all the dialogues as “flavor” and relied solely on object-based puzzles for the gameplay, but we prefer to make all the different elements of the game (puzzles, story, art, sound, etc.) work as a unit and complement each other, rather than separately creating “essential” and “flavor” aspects of the game and then trying to glue them together. So it’s more about what type of interaction feels “natural” to us in any given situation than what type we enjoy more in general. The good thing is, coordinating this is much easier with a small team like ours.

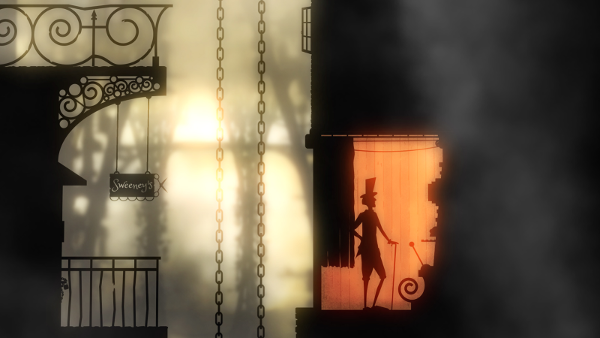

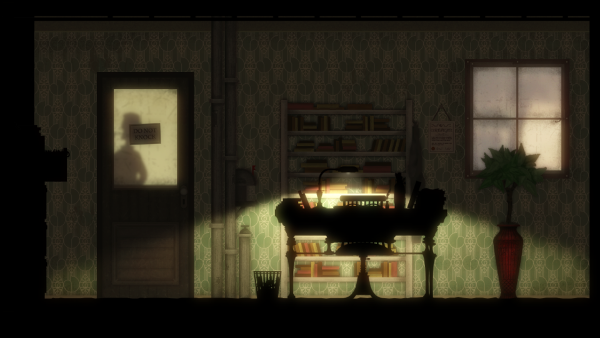

EM: The game uses color carefully, making objects that can be interacted with light up while casting characters and much of the scene in shadows. How did you arrive on this art style, and how do you see it reinforcing gameplay?

JV: Drawing everything in silhouettes sounded like a practical thing to do at first; we had (and still have) only one artist and at the time planned to have a finished game in a few months. We were partially wrong about it being “practical” though. There are many different problems and very specific challenges with having both silhouettes and non-silhouettes in a 3D world featuring quasi-realistic lighting, and we learned this quickly enough. The style was obviously inspired by Limbo at first, but minimal (non-silhouette) backgrounds soon evolved into something more complex, and we quickly moved from a 2.5D world to a real 3D environment, although most of the objects, like the characters, are still 2D. A few years later, we found out about “The Mysterious Geographic Explorations of Jasper Morello”, which is much closer to our current style than Limbo and similar games (that we have seen so far).

There is, of course, the other, symbolic aspect of all the characters being represented by silhouettes, with their features permanently hidden from the player. Their individuality is in a way obstructed, as all of them (including the protagonist) are treated by the power structures as a means to something else and not as the end in themselves, thus being symbolically stripped of their personhood.

As for the gameplay, we are aware of the potential danger this approach presents. As if “pixel hunting” was not frustrating enough in old adventures, imagine pixel-hunting with your monitor turned off, and that’s basically what could happen if we just decided to draw a silhouette of an important but small object visually overlapping (or even inside) another silhouette, so this artistic choice indirectly but drastically influences the placement of the objects and the layout of the scenes. Highlighting the object on mouse-over and using smart proximity are the most basic ways of approaching this problem, but we are currently considering some additional ideas too.

EM: The game is filled with artful wordings, from the different types of alcoholic drinks at the bar to a poetic need for better protest chants. Describe this connection to language; what goals and aims do you maintain for game writing, and what standards do you set for included elements?

JV: We are not native English speakers, so I have to admit it’s really comforting when we receive any praise concerning our usage of language. For the final game, we will hire a native English speaker to proofread and edit all the dialogues, though, so hopefully the final product will not offend anybody… at least not because of grammar. That being said, we do not plan to avoid “dirty” words completely, nor will we (in-game) try to be overly politically correct, so in this way, it will definitely offend some players (or even press), although this is of course not our goal.

The world that our game is set in is loosely based on the 1900s regarding culture, art, science, etc, and we are trying to put many references to the names of famous people, products, inventions, and companies from this time, but we won’t necessarily try to replicate the spoken language from that time. We also do this in artwork, incorporating styles like Jugendstil and Art Nouveau into architecture, design, and in-world art. But we don’t really shy away from modern-day cultural references, either, be it other games (e.g. Monkey Island, Fallout, and others in the demo), books (e.g. 1984, Song of Ice and Fire…), television (e.g. South Park), or anything else. Some players love these references, and others feel like they sometimes ruin their immersion, so we try to be careful with their number and the ways that we use them. Usually, we try not to just leave a glaring reference in there; we adapt and twist it to sound natural even to someone who might not recognize it.

EM: The game has a demo (on itch.io), and you had a successful Kickstarter, as well. How do you see these internet platforms helping indie developers, and what have been the biggest hurdles with regard to putting your work out there and interacting with the public?

JV: Even though we are very proud of our results on Kickstarter, having more than 1,000 people back us and raising over 40,000 EUR without any marketing budget, connections, or prior experience, and with only two of us working on it, the experience was extremely stressful and exhausting, and I could not honestly recommend for anyone to go that route. As we are located in Serbia, we had a lot of administrative/financial complications with setting up a Kickstarter campaign and receiving the funds afterward, but what was definitely the most frustrating aspect was a complete unwillingness of notable gaming press to mention us at all. To illustrate this: one year prior to the campaign (when we only had a short video teaser to show) Rock, Paper, Shotgun did an article about COLUMNAE, but at the time of the campaign (when we had a playable demo, an additional explanatory video, a lot of additional visual material, and text), we didn’t get a single answer to any of the emails that we sent to them. It wouldn’t be that much of a problem, if it was an exception and not a rule, but it seems like none of the popular gaming sites want any part in writing about anything Kickstarter-related, unless you are Tim Schafer or Ron Gilbert. In the end, we couldn’t have done it without help from other small studios and independent press, but even with it, we could have easily failed.

EM: As a genre, steampunk draws attention, but games like Arcanum: Of Steamworks and Magick Obscura and Bioshock Infinite take place in completely different worlds from each other (and quite different from Columnae). Describe your process in producing backstory and lore; via your updates on Kickstarter, you shared quite a lot of background writing and prototype art, so now that you’re deeper into the development process, how are you finding ways to let players into the distinctive richness that sets your universe apart?

JV: I try not to focus on backstory and lore when I work on COLUMNAE these days, because for some time now we have had more of it than we could possibly present to a player in only one game. But it still grows, anyway. For example, I might be researching a dye-making process of the period or the history of safety matches to implement in a puzzle, then continue learning about specific diseases that workers of different factories were prone to, and I end up writing about the differences between the Republic and Protectorates regarding public health care and work safety regulations. This might later come up in a random conversation with an NPC, or you might read an article about it in The Columnist (the in-game newspaper), or we might design a hospital location, or a completely new “quest” based on it. But at this moment, I never know if or when it will be used, I just write it down. We have a huge internal wiki-like website consisting of interconnected articles about the world, stories, characters, locations, and history, and even though it’s pretty inconsistent, it helps a lot.

On the other hand, as COLUMNAE is a non-linear game, we will actually only allow the player to access a little bit of the backstory during one gameplay, and different information will be revealed if a different path is taken. It will lead different (first-time) players to different conclusions about characters, factions, and even history, and after finishing the game, they may not even agree on the basic questions like who are the good guys, what’s happening inside Deus, or what is the “main quest” of COLUMNAE, because that’s how incomplete, unreliable information works. To top this off, taking a different path during gameplay will actually change the future but also the past (this is what we call retrocausality), not only regarding the character and game timeline, but also for seemingly unrelated events, sometimes set a century in the past. This means there are many possible “lores” for COLUMNAE, and all of them are canon.

EM: The elevator system uses vertical space to easily guide players throughout the level. As you’ve created unique locations (bars, photo booths, factory gates, etc), what kinds of visual and use-based criteria do you maintain? What touches have people responded to best, and what ideas have fallen to the factory floor, as it were?

JV: This is something we are still experimenting with, and to be honest, we pretty much still don’t know what will work best with players. As for geographical navigation, we will also use different maps to let the player jump between locations, and we try not to have too many long empty passages to walk through; they might be beautiful, but if you are stuck in a puzzle and are backtracking in frustration, you quickly learn to hate them.

EM: The world is filled with mechanical things and gears reminiscent of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. In terms of plot, oppositional conflict propels the story (workers versus factory owners, Deus versus Columnae versus Machina, a need for resources versus a need for clean air); describe the connection between how a game looks and how a game plays. What do you see as critical in game assets supporting the overall concept?

JV: Players will explore several different environments during the eight chapters of COLUMNAE. These will be visually distinct and will feature different forms of government, society and technology, but we are also trying to make them play differently.

Exploring Columnae (in chapters 4, 1, 2 and 5) will have a “standard” gameplay and feature graphics similar to what you can see in the demo. This is the largest area in total, but we further divide it by introducing geographical contrasts: between lower (poor, polluted, and decaying) and higher Columnae (relatively prosperous, busy, and diverse), and between the United Protectorates (conservative and autocratic) and Democratic Republic (corrupt and bureaucratic). We use smoke to portray active industry (production and growth) and smog to show its effects (poverty and pollution). Dense and seemingly bizarre and purposeless machinery signals the accumulation of wealth while empty, squatted, and repurposed buildings depict the other side of that coin, an impoverished majority on the permanent brink of survival.

Other environments will have their own visual feel but will also feature a slightly or drastically different gameplay. In Machina (chapter 3), it’s repetition: you will struggle with navigation through an endless maze of dark passages and almost identical rooms, using only unclear, contradictory, and circular verbal instructions, while encountering what seems to be the failing memory of the protagonist and a complete disregard for common sense among other characters. In the futuristic, active, and orderly Greenhouse Dome (chapter 7), which is still under construction, you will try to infiltrate a prosperous clockwork-like society-corporation built in the middle of the wasteland, but will struggle with communication as everybody is too busy to talk with you. And on the sunny Cliffs (chapter 6), you will discover a rural anarcho–tribal society, only to be dragged into a spiritual, drug-induced experience, including a series of visual changes which will allow you to access and notice objects previously unavailable, along with cause/effect reversal, which you will have to embrace to successfully solve the puzzles.

EM: Problems stemming from the Industrial Revolution, corporate greed, and continuing environmental problems connect the game world to our present-day planet. Players will certainly pick up on this, but how directly do you intend to make this connection? Do you intend the game as standing completely apart from the world we live in or as a way to view our modern challenges from afar?

JV: Class struggle and the detrimental effects of capitalism are among the main themes of our game, and they are as central to the world of COLUMNAE as they were to the real world during the 1900s (and as they are to today’s world, as well). So there is no need to really spell out this connection any further: their problems will be by their very nature very relatable to us, because they are in essence identical to ours. Some players may not be so interested in this side of the plot, so they might try to ignore it or pursue “non-political” goals for the protagonist, but the effects of harsh reality will haunt them constantly and might kick them when they least expect it, as they do in the real world.

Here’s the trailer, in case you missed it: