Interview: Eon Break’s Artyom Vorobyov

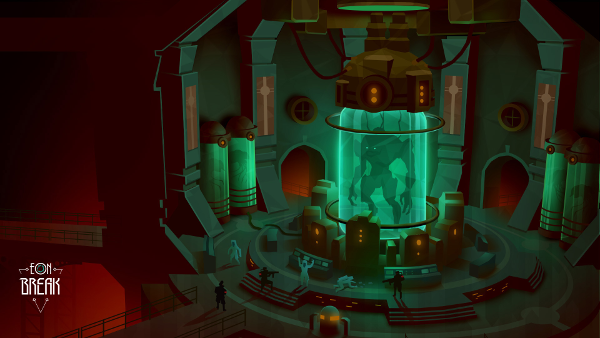

Indie games strive to hit all the pleasure center buttons, and Glad Rock‘s sci-fi platformer Eon Break mixes neon 1980s art stylings with a 1940s dieselpunk world featuring Nikola Tesla (and it only gets wilder from there). With a Kickstarter campaign in full swing, developer Artyom Vorobyov chatted with me on the various facets of the ambitious project.

Erik Meyer: First of all, Tesla fighting Nazis in an alternate WWII (not to mention insidious mushrooms) makes for quite the metroidvania scenario. But Tesla does get a lot of play these days, as do Nazis and alternate histories, so I’m curious about the elements of your universe (and the gameplay it inspires) that have pushed you creatively. What are you adding to the alien technology/quirky gadgets/time travel weirdness that will hit the sweet spot for audiences?

Artyom Vorobyov: Tesla, Nazis, and mushrooms in the alternative history describes only the top layer of the game world. When you dive deeper, you’ll understand who’s the real antagonist and what is going on. Actually, to reveal the full story, you’ll need to complete the game several times, choosing different paths and getting different endings.

The game is full of puzzles, and the biggest of them is the game world itself. You’ll have to reshape it in order to ‘solve’ the game and get the true ending.

Talking about world reshaping – the game revolves around Apparatuses. These are special devices that grant the main hero various abilities. Each major apparatus allows either space control or time control in some way. For example, the Tesla Gun can be upgraded with the Void technology. This will allow it to consume (and return) various small objects. You’ll be able to consume a crate and place it elsewhere in order to find higher ground. With more upgrades, it will be able to consume projectiles, enemies, and even entire locations that can be later placed in other parts of the game world. This way, the player will be able to reshape the world and access new locations.

EM: The game’s art style (bright color palette, retro sound, and sculpted look) combines with precise platformer mechanics and unlockable technologies to drive the experience. What kinds of challenges have come with the creation of assets? What kinds of things have come together quickly, and where have you faced hurdles?

AV: We spent quite a lot of time searching for an art style that looked awesome, fit the game style, and together with that was easy to create (there’s only one artist in the team, and we thusly couldn’t afford to create very complex assets). In the very beginning, we defined a range of requirements for the art, including slicing principles, that allowed us to build complex locations without creating a huge amount of assets. Then, Alex (our artist) spent several months creating sketches that fit all the requirements – that was the hardest part. Every sketch felt like not quite what we expected. Until one day he did what we called PolyVector – a 2D location sketch in a vector style that looks like it consists of 3D polygons.

After that, everything went smoothly.

EM: I notice a lot of small details in the levels (swaying lights surrounded by animated yellow rings, turning vent fans, bubbles rising in suspended animation tanks, etc); you mention the visual design/hand drawn aspect of what you do on your Kickstarter page, and I imagine this can be quite time consuming. As you’ve created each location within the game, what does your planning and implementation process look like from a practical, team-oriented point of view?

AV: As I’ve mentioned, our art assets fit a range of requirements. Most aspects of these requirements are dictated by our level editor. It’s our secret weapon – an add-on for Unity that allows to build 2D grid-based locations super fast. It was created specifically for Eon Break. The main idea behind it is to make the editor responsible for routine operations, like connecting tiles so that their patterns will fit one another.

It works similar to Photoshop – you choose Brush (let’s say Ground) and start to draw like you would do in Photoshop. Tiles are placed on the grid and adjust their positions and patterns automatically, colliders are added automatically, grass appears automatically, and so forth.

So once an art asset is created and added (like Cave or Lab), you can switch to it and simply draw the location.

From the team point of view, there are only two team members involved in the world creation. Our game designer plans locations on paper and then creates the physical layer in the editor, and the artist creates assets and adds all other layers and decorations to the locations.

EM: Crowdfunding requires a great deal of endurance, and your Kickstarter campaign gives a lot of information about what you’re up to. Describe your experiences engaging with the public via that platform, and what kinds of responses have you been getting?

AV: We were really surprised by the level of Kickstarter audience engagement. People really care. We’ve received a lot of positive feedback, especially on the art style, the story, and the mechanics. There were a bunch of suggestions for game improvements. Also, we’ve received really useful advice on how to drive the Kickstarter campaign. Communication with the audience gives us the energy to move forward.

EM: Having the game pick up at the moment of Tesla’s death makes for an interesting wrinkle; as you’ve tweaked history and added things like the discovery of the Angel, what has kept you grounded in the process of creating a continuum of characters and events? Throughout the development process, what kinds of changes have you made to the game’s story?

AV: Actually, the story was dictated by the game mechanics. Eon Break was born when we (the core of the Glad Rock team) decided to make a metroidvania that will be played differently from the typical games in the genre. So in the beginning, there were time and space control mechanics, then we created a prototype to see what’s working and what’s not, and only after that have we added the world, story, and characters to the game.

The process of building the story and characters was long and quite hectic. There were alien planets and heroes, far future and spies, cyberpunk and robots. We’ve spent many months trying to define how we want our game world to look and feel. But everything changed when we understood that Nikola Tesla ideally fits the hero spot. We were looking for a hero who can invent things (build apparatuses) and kick asses at the same time. Somebody similar to Tony Stark. Once we thought about Nikola Tesla, we were unable to imagine another hero for our game, so we built the entire game around him!

EM: I’m interested in your process at Glad Rock and your level of coordination between the team on the project; how do decisions get made, and with a delegation of duties, how do you all communicate? If one person brings an idea to the table, how does that idea reach the point of implementation?

AV: We’re small team and everyone can talk to everyone. But still we have some processes and fields of responsibility. For core game aspects (overall art direction, mechanics design, the plot, level editor, etc.), we have an agreement on who makes the final decision in the case of a disagreement. Global questions are discussed by the entire team, and we vote.

As a rule, we’re coordinating our plans on regular Skype calls. Thus, we share work status, present ideas, define priorities, assign tasks, and discuss deadlines.

Regarding ideas – we discuss potential positive outcomes and measure the costs. If the outcome isn’t clear, then we create a small prototype to try it out. If the team agrees that the outcome is worth the effort, we convert the idea into tasks and implement it.

EM: When it comes to side-scroller mechanics, what do you see as essential to providing gamers with fast-paced experiences? What kinds of personal preferences do you have, and how do you make things just difficult enough to be satisfying without crossing into the zone of frustration?

AV: We’ve put a lot of thought to the difficulty aspect of the game. On a basic level, we want to provide a fast and smooth experience. There are three main activities in the game – movement, combat, and puzzle solving – and movement is the king among them. It’s almost like in Super Meat Boy – if you move correctly, then you’re able to pierce through almost any location without a single stop. A variety of abilities allow different approaches for every single room. But this non-stop movement action requires quite developed skills and reaction, so the main game can be as difficult as you want it – will you dare to pass a vertical-oriented room with only wall jumps and teleports, ignoring the elevator? If you succeed, you’ll be able to collect a time-restricted bonus, but in case of failure… well, a save room may be not be that far away.

Moreover, there are a lot of optional paths and quests for those seeking true challenges. Really skillful players will be awarded with more upgrades, new apparatuses, and secret story insights.

EM: Within science fiction, almost anything is possible. What kinds of things have you had to leave out, simply to keep the game balanced, and what elements will give Eon Break high replay value?

AV: A lot of game mechanics, tied to time and space control, have been prototyped and later removed from the game. Some made the game too slow, some were hard to explain, and several didn’t passed our move/fight/think test – in the game, every major mechanic/unlock allows players to perform better at all their main activities – move more effectively, fight enemies, and solve puzzles. At one moment, there were just too many mechanics in the game, and it was hard to control the character, so a good portion were cut out to make the game balanced and easy to pick up.

Regarding the replay value – there are several endings in the game, and one of them can’t be achieved on the first playthrough no matter how hard you try. Moreover, there’s no way to build and upgrade all your devices on the first run.

Here’s the trailer, in case you missed it: