Interview: Conarium’s Onur Samli

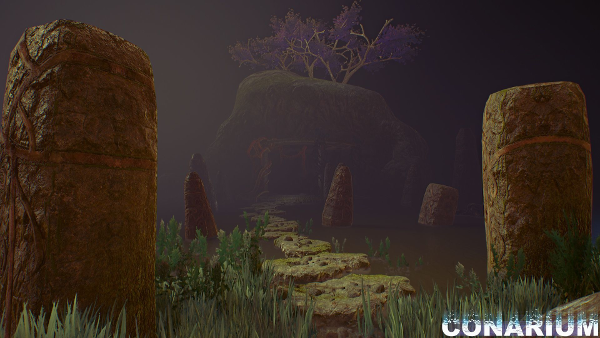

For supernatural/Cthulhu mythos adventure game fans, Zoetrope Interactive‘s release of Conarium adds an insightful and well-turned chapter to existing canon, taking players on a voyage of madness, ancient artifacts, and strange devices; I chatted with developer Onur Samli on the many development facets that brought the project to life.

Erik Meyer: The game drops us into the life of Frank Gilman, a member of the Anthropology Department at Miskatonic University, and we quickly transition to mishap on an Antarctic base. Players explore the pitfalls of consciousness expansion, and the game world draws from a Lovecraftian universe rich in lore and history. As you’ve made Conarium an experience in and of itself, what lessons do you take from previous games in similar settings, and where do you see your work leaving its mark?

Onur Samli: The first and foremost lesson we learned was the obligation of the flawless nature of any kind of narrative media out there. Games should be exoteric – easy to follow up – for the players to grasp the essence of the plot. Story is the second aspect we focused on because plot rounds up the general fictive form and shapes the overall experience in a greater way. I cannot say we did it perfectly, but we tried very hard in this aspect for a smooth playability. And about leaving a mark, actually we don’t think we can leave any possible mark behind. About what makes Conarium different from other Lovecraftian titles, I can say that the style of narrative we chose for our games is the only one.

EM: As a follow-up, Zoetrope Interactive already has a following due to two previous Darkness Within titles. What does it mean, having several games under your belt? What lessons have you learned from the previous titles, and how have you developed as a studio?

OS: For us, having several games under our belt is just an indicator of the gathered experience and points out the knowledge we acquired throughout all these years. Actually, the lessons we took from our past two games were mostly on the technical side of things, like managing the whole project with a small team and proper usage of limited time. Other than this, in Conarium, we used the same narration method we used with the DW series, which is mainly the foreshadowing of future events. We find this mode of narrative is very effective since it is always impossible to convey what you have in mind solely with the visuals.

EM: Conarium demonstrates mechanics that aid in exploration (a glowing stone clears vines from a path but requires charging; switches need to be activated to unlock new areas). What other in-game mechanics do you see as providing immersion for players while encouraging them to soak up the game’s story? How do you best provide compelling, yet limited elements while rewarding the act of adventuring?

OS: I can say the mechanic of tearing down some obstacles with an axe in order to gain access to some secret areas which let players immerse themselves into the atmosphere of the game by providing trophy items which belong to a civilization long gone. I think, on the aspect of narration and immersion, when players achieve something on their own and discover something related to the story, they simply sink into the plot more and more.

We decorated the game world with Lovecraftian details and lore in the fashion of sculptures, bas-reliefs, visions and documents. Other than that, we hid some special objects in secrets areas that can be found by players if they carefully explore the game world. We use this as a reward for the curious players who take the trouble to search high and low for what the game would offer to them.

EM: The game’s story provides unique, disjointed locations connected by darkness and disorientation. What do you see as essential in uniting these experiences? What devices do you find yourself relying on, as a developer, from a writing perspective?

OS: Disoriented places and times are just ideas we think best suit a Lovecraftian game, which on its own terms supports the notion of madness and bits of sanity. Most postmodern literature, and even H.P. Lovecraft himself, uses this narration a lot in stories, and by doing so boosts the atmosphere hugely. Stream of consciousness is the most important narrative device we used to describe the past events rather than telling them unnecessarily via papers and documents. Relying solely on documents was the most important aspect we needed to avoid using because documents can only give background information about the not-so-important events, and anything pertaining to story development should be given visually. Foreshadowing is another device we use generally, because it greatly shapes the events that are going to happen or just happened moments ago. This ignites the player’s imagination in a positive way.

EM: The adventure combines prehistoric shrines and retro-futuristic technology, modern psychology with ancient supernatural evil, and nostalgia with horror. As you’ve incorporated assets into the game (music, art, etc.), how have you worked to maintain a consistent world view?

OS: In the beginning of the project, we defined the absolute design pillars of the Conarium. This is something very important and was used as a guideline throughout the project. Then we built the assets around this pre-defined frame. So as the game design was shaped, consistent visual style became clear in our minds. H.P. Lovecraft wrote his stories against the backdrop of the modernist movement. So we simply imaged how he would react in creating visuals of the game in the perspective of this context. Finally, we thought it best to incorporate the past with retro-futuristic technology.

EM: Any time a narrator changes perspectives or experiences hallucinations, an audience may baulk at the notion of an unreliable narrator. To what degree do you feel the need to address this aspect of madness, and what steps ease transitions? It it easier to deal with insanity in electronic media than it would be in a novel?

OS: As in most of postmodern literature, dysfunction and personality disorders usually diffuse into the pattern of narration which creates ambiguity, mystery and tension, resulting in a confusing storytelling technique. To dispel the mists of confusion, the game world should include clues about the story and the plot, enough to satisfy the player’s urge to understand. We try to be as clear as we can be and scattered clues and notes here and there to help players in this aspect. In the perspective of movies and games, actually dealing with insanity is very different and works differently. For example, books rely mostly on the aspect of your imagination, and in the hands of talented authors, creates a feeling movies and games cannot compete with. Movies and games on the other hand should deal with the visual limitations, and even it is done right, it leaves feeble marks in contrast to a book.

EM: As a studio populated by three developers, Zoetrope Interactive is chugging right along. What advantages have come with being a small team, and what does your workflow look like? Where do you see indie developers succeeding, when compared to larger companies?

OS: Actually, there are not many advantages, other than there is no bureaucracy and the profit is shared among a small number of people.

We do not have a fixed pipeline. Because we are a very small indie team, we generally need to make things that are out of the area of our expertise. And this makes it very hard to make set-in-stone decisions for some aspects of the game.

I believe the success of prominent indie developers comes from the unique game design choices they make while developing their games, always keeping in mind that the fun factor is very important for a game.

EM: You mention At the Mountains of Madness as a key inspiration, but describe the kernel that started Conarium. What did the project look like early on, and as you’ve made judgment calls, what kinds of things have you had to leave out, and what did you fight to keep in?

OS: In the early stages, the project was different from the final product, we set about creating a more interactive exploration experience, but we needed to leave lots of things out in order to keep the project in feasible limits like removing some character animations and new music tracks that would have taken a long time to compose and record. We tried to keep in the things that make the experience a Lovecraftian one, like some special 3D models, a variety of environments and the quality of writing of the in-game texts.

In case you missed it, here’s the trailer: