Interview: RITE of ILK’s Alanay Çekiç

A co-op game that sends two kids into the unknown on behalf of their people, Turtleneck Studios’ RITE of ILK combines collaborative play and beautiful environments, already garnering game award recognition while turning heads. I chatted with Creative Director Alanay Çekiç on his process and project goals.

Erik Meyer: The mechanic whereby gamers play two children tethered together sets RITE of ILK apart from other games, so I’m interested in the genesis of this unusual feature. Did the project initially revolve around building a world and puzzles to utilize this type of experience, or did you come to this type of connectedness by way of the game’s story? What kinds of design challenges have come with the two-player model?

Alanay Çekiç: That’s an interesting question. We were never out to reinvent the wheel, but we started our endeavor by wanting to commit to something innovative and meaningful. With that ideology in mind, we had several, sometimes quirky or weird ideas worked out in our designer’s little booklet or in the shape of raw linework in our artists’ sketchbooks. I remember how RITE of ILK in its very first draft was a 2D side-scroller, much akin to popular 80’s duo Ice Climbers. It didn’t last beyond a few hours before we switched to 3D and a more open-world feel; after all, half our team consists of ex-Triple A game studio collaborators. When the idea of physically tethering two characters came up, we were immediately charmed by the thoughts of mentally tethering two players as a result. How far can we push two very possibly distinct different people and how will it affect their developments? Although the idea immediately pulled us in and appealed to us, it also gave birth to questions surrounding the idea. How interesting and engaging can we keep gameplay when it’s about rope? How many puzzles and intriguing elements can we add to something like this? Co-op is a relative niche; will we be able to sell well enough? And most importantly, how are we going to design a single player experience for two people while keeping co-op intact at the same time?

EM: It strikes me that having to work with another player creates an environment of cooperative learning, so much as basketball or canoeing help teach teamwork skills, how do you find yourself playing to the strengths of ‘togetherness’ as a developer?

AC: It’s a fundamental part of our design cycle. Every gameplay loop or sequence is inevitably judged by whether it contributes to the overall or specific co-op experience. Whether that contribution is a mental challenge, emotional sequence or fun quirk, every part of the game needs to be interesting to both players, regardless of whether that specific sequence is more focused on one character or player. It’s not unusual to find blocks that are pushable by only one player, just as there are bigger blocks that require the strength of both players. We cater to the individual and solo experience, but ultimately, it’s a game for two. We thoroughly test the game with a variety of partnerships; couples, brothers, sisters, grandchildren and grandparents, parents and kids, and even strangers. Going on an adventure with someone you know or don’t know is memorable, and the game will feature a wide-variety of challenges to test several teamwork skills.

EM: Simply said, the game’s visual assets are beautiful, but aesthetic choices strike a balance between reality and fantasy, so what guides your development in achieving the kind of look that harmonizes with the overall experience?

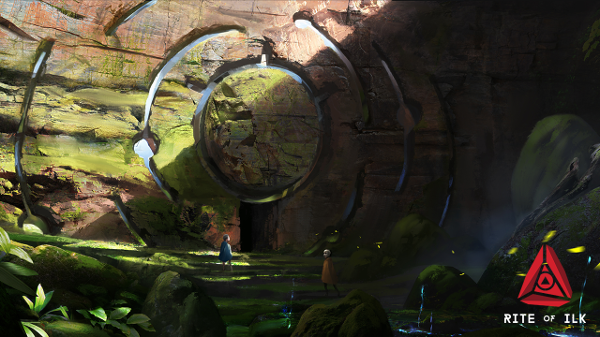

AC: Because our game plays out in a lot of dense and versatile areas – from lush jungles to snowy mountains – we wanted to work with reduced noise and went for semi-realism. The world needs to feel vivid, appealing, and fun to explore, which is why we went for slightly harsher lighting and saturation. Our development team desires for areas to be magnetic and when a player sees it, he’ll be like, “Wow, this looks great!” Every nook, corner, and cranny of the Azath world needs something daring to the eyes, which will make you want to jump or crawl on it, discuss it with the other player, and explore and discover. There’s always something new to find and talk about.

We concept a lot of our areas, and even the smallest of plants has been thoroughly discussed and improved at one point in time. We use smart tricks to make the world feel more interactive and alive. In the grand scheme of things, our ideology is to have a world that feels earthly enough to be recognizable, but unique enough to represent a vastly different planet.

EM: Perspective wise, we watch the game from above the characters, and I notice in some of the early gameplay that cameras would shift quite a bit while moving between areas, so what do you see as the key to smooth transitions in cinematic play?

AC: There are smart film-proven techniques to do it, such as having a zoomed-in shot and being somewhere else entirely with the next zoomed-out shot, putting an emphasis on the emotions on a character’s face to distract from shifts, starting your cinematic sequence with an environmental overview shot, timing it together with dynamic movements, etc. There’s a lot of technical jibber-jabber that can be used as an explanation, but at its core, I believe it’s about feeling natural. A transition should, unless you’re looking for it, just flow and happen.

EM: I’m interested in your workflow process and how ideas go from concept to implementation at Turtleneck Studios, so maybe you could walk through an example?

AC: I don’t want to make the explanation sound too convoluted. With that in mind, the following example only includes the art, concept art, and design teams.

The design team comes up with an idea, let’s say, “Characters should be able to be lifted up by air in x area.” The concept art team gets instructed by the creative director and management team to work on x area and to keep in mind that ‘characters are able to be lifted up by air in this area.’ The concept team works on it and after extensive research figures, “Hey, let’s create a leaked pipes system to complement air gusts that lift up the character(s).” Concepts fly out (pun intended) and everyone’s (yes, everyone’s) feedback channels get flooded by concepts for x area. Programmers, graphic designers, leads, interns, everyone’s input is welcome and, to a certain extent, listened to, although final decisions are made by leads and directors.

After collecting input, more precise art direction is given by the art director, and the concept team now knows what to do with all that input and how to channel it into their work. This leads to the conclusion, “The pipes system is cool, but it needs to be communicated more clearly. We need a specific material for pipes, clear shapes to identify them from a distance, and large cloth spanned over buildings so that players can see the strength and effects of the wind on the environment. The gusts still lift up the character(s).” While the concept team starts working on new concepts that incorporate feedback, a designer starts tweaking his design-blocking to loosely follow concepts and art direction; this gives him the time and opportunity to test out an improved and art-tested design. While the concept artists and designers are busy, the rest of the art team doesn’t just sit idly by but keeps themselves busy, figuring out what materials could work, how to lead players from A to B, how to tackle streaming and level set-up, and – after design finishes their design-blocking – starts art-blocking the entire x area from the design-blocking up.

When the concept team finishes their latest variant of x area, the art-blocking gets revised and the three teams (art, concept art, design) communicate hence and forth in order to improve the area’s visuals and flow. Overseen by creative direction, the teams strive to strike a fine balance between visual appeal, accessibility, and game design. In the end, “X area is a tested environment with a unique pipes system that communicates clearly, has specific cloth spanning buildings and objects that respond to gusts of wind, includes intentionally placed holes in some pipes through which gusts of wind leaks, and encompasses puzzles and challenges that take advantage of these wind gusts to lift a character up higher.”

It’s a pretty intensive workflow that literally keeps everyone busy, but it also allows for creativity and different perspectives to be heard and seen, ultimately improving the game.

EM: Additionally, what does it mean for your team that you’re located in Utrecht, the Netherlands?

AC: The Netherlands is a small country and there aren’t many game studios here. Being located in Utrecht, the center of the Netherlands, allows for easy accessibility. Utrecht’s railroads and transportation services all lead to Utrecht, which makes it easier for our team members to travel to and from our office. Although there aren’t many game studios, most indie game studios and Dutch Game Garden and DGA are located in Utrecht, so that makes for a cool bonus.

EM: Over the years, I’ve found myself drawn to cooperative board games and hobbies, as opposed to competitive engagements, and I certainly don’t think I’m alone in this, but if you were to describe other concept and learning goals you have for ROI and its narrative experience, what would those design elements be?

AC: That’s amusing. I can definitely find myself in that notion. Whereas I used to be attracted to competitive board games such as PayDay, Risk, and Monopoly, I am now much more inclined to play board games like Legends of Andor in which you have to play together. I don’t think it’s a ‘growing old’ age thing, time just generally changes preferences. I used to hate broccoli, now I love it, and perhaps in twenty years I’ll find myself hating it again.

In its essence, ILK is a cooperative game. But it’s not just one big world with one design. The world used to be inhabited by rich people, poor people, people with different types of housing; small or big, with different interiors, materials, and textures. We have a fantastic document that defines what kind of materials are used where, which people used to live where and how, and more — there’s a lot of back-story there. We want to indulge the players with a world filled to the brim with new findings and lore, complete with engrossing stories and take-aways.

We have a very involved journey that highlights the two children and their interactions with one-another. The way in which each character interacts with the world will be vastly different. Mokh might be interested in a certain object, environment, or creature, while Tarh might not like those same things at all. We want their personalities to stand out. You pick a character and you’ll go through the whole experience with that persona. But outside of the screen, we want the players to be able to dictate what their own roles are. The gameplay abilities are the same, but the way a player chooses to interact, their involvement and emotional journeys, their approaches to gaming — aggressive or slowly — will all be different from their partners. We won’t hinder players to adjust to a play style that suits them, instead, we encourage players to be whoever they want to be.

EM: Describe the online multiplayer component of ROI; how are you translating the two-player exploration adventure into a set of multi-two-player challenges? What different mechanics or game tweaks come with making levels have depths beyond simple speed runs or king-of-the-mountain scenarios?

AC: Although you could just speed-run the whole game if you wanted to, it’s not a game designed for speed runs or king-of-the-mountain scenarios. The game contains an immersive story in which your actions have meaning, bound in a world in which you and another ilk struggle to overcome challenges together. It’s not your run-of-the-mill co-op game.

The online multiplayer component of RITE of ILK is identical to its local multiplayer counterpart. The whole journey is playable online with a friend, family member, or even a stranger, and is playable through chapters.

Not everyone has friends laying around, ready to pick up a controller and start playing at their leisure. If you want to play by yourself, you can do that through the multiplayer feature, which will connect you to another person in a likely similar situation.

There’s always the opportunity to play online with people you do know. In case you play together with someone you don’t know entirely, it allows for a different type of bonding and connection. You’re getting to know a person you didn’t know before, whom you’ve never seen before. Albeit wishful thinking, perhaps even a friendship could blossom, who knows? Whether you’re playing locally or online, you’re still playing with another person. The crux of the game embodies teamplay and going through a journey with someone else.

Playing online does make communication, which is crucial in teamwork, a definite focal point in development. We haven’t worked out specifics yet, but there will be ways to communicate with your teammate and be serious or silly together, even without directly inserting words or speaking yourself.

We believe that the multiplayer aspect of RITE of ILK is going to contribute to the magic of playing with another ilk.

EM: Many of the game’s most striking details embed themselves in the environment, such as puzzles etched in the sides of cliffs or the plant-covered buildings falling to ruin, so do you see a need to create an aura of wonder and mystery guiding these decisions, or is there something altogether different at work?

AC: The world’s aura of wonder is an intentional decision to drive player exploration. The Azath world lends itself perfectly for that and makes it exciting and refreshing to walk around and unravel mysteries.

In case you missed it, here’s the trailer: