Interview: Once Upon A Coma’s Thomas Brush

Crowdfunding can be fickle, but it should come as no surprise to anyone familiar with Atmos Games owner and art director Thomas Brush (think Pinstripe) that Once Upon A Coma didn’t take long to blow through its initial goal (not to mention multiple stretch goals). Gamers play Pete, who awakens from a coma to discover the world isn’t as he left it, a landscape filled with massive insects, naughty children, and a host of forts, puzzles and other challenges. I chatted with Thomas to divine the current state of affairs, noting his unique, polished art style and keen attention to detail.

Erik Meyer: When last we chatted, Pinstripe had just launched, and you’ve since described how stressful that time was for you, so from that time until now, what experiences have eased your life most as a developer? Was it as straightforward as needing extra project help and being able to delegate tasks, or are there other aspects of your work that have had epiphany moments?

Thomas Brush: I don’t think the stress was actually as bad as I thought it was, especially in hindsight. A lot of the stress was just because of fear and anxiety, but there wasn’t too much work to be done, because we had already done a lot of quality assurance testing and whatnot. So, things weren’t as stressful as I thought.

Now, I don’t really worry as much about games. I realized that for me and my personality, things work themselves out, and I don’t really have to be afraid of things breaking and things not going well on launch. I have a great team and work with a really incredible publisher, so I don’t really have to be as worried. I also have a developer. His name is Erik Coburn; he is very particular in a good way about making sure the code is solid and won’t break.

Was it as straightforward as needing extra project help and being able to delegate tasks? Yeah, I think it was that, and as I said earlier, I think it was growing emotionally as a person and learning that I don’t have to worry about every single thing. I’m at a point now where I’m spinning so many plates that I’m okay if some of them break.

EM: With Pinstripe, work was solo; you’re now joined by Erik Coburn and Serenity Forge Studios, who provide things like coding help. In terms of your daily process, how does this free you up, and what tasks move along faster as a result? Conversely, what kinds of communication now have to happen?

TB: Everything is so much easier. With Pinstripe, I spent the majority of my time coding, even though on the surface, the game is very artsy and beautiful and story driven. Most of the work was done on the code side, mainly because I don’t truly understand code. My schedule is truly free to let me be a marketer, a musician, and an artist, and I really enjoy doing those things. But now, Erik and I have to make sure that we communicate properly, especially because I’m more entrepreneurial and he’s more schedule oriented. Both of those hats are perfect and really important to have in business and in game development. I have to make sure that I tone down my energetic entrepreneurial tendencies, and I’m so glad that Erik helps me do that, because we certainly don’t want the schedule to go off the rails.

EM: Your Kickstarter campaign for the project is blowing up. You obviously put a lot of time into not only your work but how it gets presented via social media, your website, and crowdfunding. It seems to me that your gifs, screenshots, and videos tend to (beyond showing a lot of polish) demonstrate your process – for example, going from a sketch of a scary adult (the ‘pissy zombies’) to a clean version. As a developer, what things do you balance when pulling back the curtain for your audience? What parts of your story do you see as essential and intriguing to both uninitiated and returning audiences?

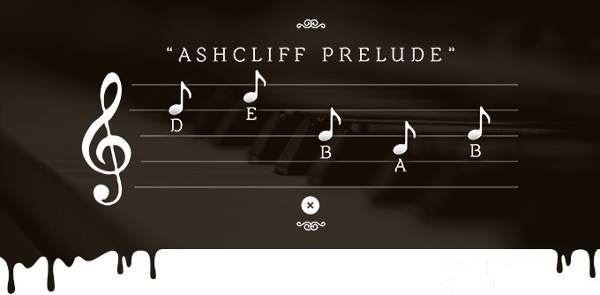

TB: So I pretty much tell everything to my audience. I want to be transparent and open, and I want to include them in the process. So, for example, I wanted to show them how I write music. And show them how easy it is and that I’m not really special. I just know how to use software. So basically I had each of my Kickstarter backers pick a random note on the piano. And I plugged them into my software to show them how you can make a complete array of random notes sound beautiful, and I uploaded that as a video on YouTube, and people really enjoyed it. You can search that, if you want, on my YouTube channel. So I really want everyone to know what I’m working on and to be transparent. And show them that making games is hard work, but it doesn’t require you to be Einstein or anything. It’s pretty straightforward.

Both uninitiated and returning audiences need to experience what the original Coma had to offer. It has to have that same feeling, same general emotional story. The specifics of the story I never really worry about, but I make sure the emotional note, the tone that the story strikes emotionally, is the same one.

EM: Much as Bill Watterson, Berkeley Breathed, or Gary Larson (to list a few favorite cartoonists) developed their own drawing styles, so does your work maintain a unique visual feel, so at a time when the artistic qualities of videogames can be breathtaking, we also see a lot of games that (be it playing mechanics or assets) feel derivative; in terms of creative freedom meshing with functional game requirements, what has contributed the most to your development and success within the digital medium?

TB: I think what you’re asking is how does digital gaming functionality mesh with the more artsy emotional side of gaming, and I’d say that I’ve always had trouble making them mesh. I tend to focus on the creative side of things. What I mean is the storytelling and the music and the emotional side of things. Fortunately, in this case, Erik Coburn has been helping me focus on the development side of things and the mechanics side of things. Also, we have a budget and a schedule this time around; we did for Pinstripe, but I didn’t really follow it like I should have. When you limit yourself in that way and stick to those limits, you can be really creative with gameplay mechanics that are already built and expanding them. So it’s always a challenge mixing the functionality of gameplay mechanics with the emotional side.

EM: The production cycle for Pinstripe took a long time, and you’ve described the process of overhauling some of those early learning years as your work came together. With OUAC, what has your process/pipeline been like, as you’ve been through this rodeo before?

TB: I’m not as spastic as I used to be. When I have an idea, I tend to sleep on it and wait for that idea to sink in, and if I’m passionate about that idea a week later, I’ll pursue it. And by pursue it, what I used to do was build it all out and finish it, and then hope that it looked good and felt right, but now, Erik and I will concept things out and make sure they feel right, so we take a lot more time in preparation of doing something than I used to. I used to jump right in and see if it worked, and it rarely did. That’s why I threw things out so often.

EM: The impetus for OUAC comes out of Coma, your previous title, so as you’re working within a universe you previously created, can you describe the task of creating the new iteration? What have you learned in hindsight, and what lessons come from reentering a familiar space?

TB: I can tell you what I’ve learned is that if I don’t like something about the original Coma, I can’t just throw it out. The reason why is that my opinion about why the game is good isn’t actually the most important opinion anymore. The most important opinion comes from the audience, so if millions of players across the world really, really like what I see as a terribly executed trampoline that launches you into space, and the graphics are horrible, and I don’t like that part of the game, but everyone likes it (and by the way, that’s from the original game), I should probably put that somewhere in this next game. But what I learned is you can put the original intention into the game of something that people really loved from the original, but you can change it a little bit so that you don’t go insane, so for me, I feel insane when I want to remove something from the game that I don’t like that I feel is hurting the game, but I know that I can’t, so instead of just removing it outright to satisfy my brain, I will change it slightly and hope it makes me feel a little bit better.

EM: You’re releasing the game on a variety of platforms across a range of operating systems, including (per the recently-met stretch goal) a Switch version, creating a number of different hardware and software environments. I maintain a Windows laptop and a Ubuntu workstation, for example, and specific drivers and video cards can make for oddball framerate experiences, bugs, and interesting workarounds in some indie titles. As a developer, are you sometimes nostalgic for a time when limited configurations made for less *known* concerns, or do you see modern engines (with an ability to release across a range of devices) and a high level of professional standards as the antidote to glitchy experiences?

TB: I don’t think limited configurations were helpful. We were in a really weird spot from 2007 to 2014 or 2015, where there was a huge array of devices, and they all sucked a little bit. Like the iPad was slow, and the iPhones were slow. Certain MacBooks were slow, certain laptops at certain prices were slow, but now everything is so fast, so for 2D games, it’s really great, because Unity allows me to port to all of these, including a Windows laptop with Ubuntu, and I don’t have to worry about it working, because Unity pretty much makes sure that it works for me. What I mean is they’ll throw console errors in the Unity editor, even if I’m building for Windows; they’ll tell me an error that would probably happen for Mac or Linux as well. So there’s a level of strictness that helps with development. So no, I don’t have any nostalgia for those limited configurations, because frankly, those limited configurations were slow. Even though there was a small amount, they were slow, and you had to build for each one. That’s why you had one version of a game on Playstation, and then when it came out on Xbox, it felt totally different, looked totally different, because they were building for completely different platforms, whereas now, things have kind of blurred across platforms. Basically, everything is just similar hardware, I think.

EM: All of your work incorporates music in beautiful ways, so as the game teaches songs written by the protagonist’s sister, what levels of depth do you see players gaining for a crossing of the senses (audio, visual), and what philosophy directs your melding of the two?

TB: I don’t think I’m going to go any deeper than what Zelda did. I think this is the one part of the game where I just want it to be simple and clean. I don’t want to be clever. I just want to do a simple learn this song, get this ability. I think people really like that, and I think honestly people have craved that kind of gameplay mechanic for a while now, and I’m happy to put that into OUAC. Regarding the philosophy of blending audio and visual, I always say in my head, there’s no difference between the music and the visuals. They’re one. That’s why you don’t call separate parts of a season something. It’s just a season. A season like spring includes the sound of the birds, the sound of the wind blowing through the brand new leaves. It includes the smells, it includes the sunshine in the blue sky, and the green grass. It’s all one thing. When spring comes, you don’t think of one specific part, it’s just one giant feeling, and that’s the goal with music and visuals. It’s just one thing, and for me, I call that atmosphere.

In case you missed it, here’s the trailer: