Interview: El Hijo’s Jiannis Sotiropoulos

A spaghetti-western stealth game that follows a child questing after his mother in a world of outlaws and desert landscapes, Honig Studios’ El Hijo captures the flavor of storybook Americana. With saloons and a monastery, the project evokes a sun-baked mood across a journey of discovery, and I had the fortune to chat with developer Jiannis Sotiropoulos on the vital elements driving his work.

Erik Meyer: El Hijo drops players into the role of a young boy seeking his mother in a mythical American west that includes irony and sarcasm, so what was the genesis of the project? What led your focus towards stealth/puzzle solving?

Jiannis Sotiropoulos: “El Hijo” is very much inspired by Alejandro Jodorowsky’s “El Topo”, specifically the very first scene of the movie where the father asks his 7-year old son to bury his first toy and be a man.

In the game, we’re telling the coming of age story of this boy, starting on his own in front of a monastery gate where is mother leaves him behind. His ultimate goal is of course to find his mother in the neighboring town, but first he has to sneak his way out of the monastery and through the desert.

It felt natural to focus on stealth mechanics, since a small boy can only use tricks and pranks, and must remain hidden from view in order to sneak around enemies who would otherwise easily overpower him.

EM: Art assets use warm, earthy colors and organic structures with clean lines complemented by shading that follows the geometry of walls and windows. What has guided the project’s overall graphical look/feel, and how did you arrive at the current aesthetic?

JS: The atmosphere is drawn by Sergio Leone’s westerns and the aesthetics from Saul Bass and German Expressionism. We still wanted to create an environment that is majestic and not empty and torn down. The ancient city of Petra in Jordan and Antelope Canyon in the U.S. were great influences.

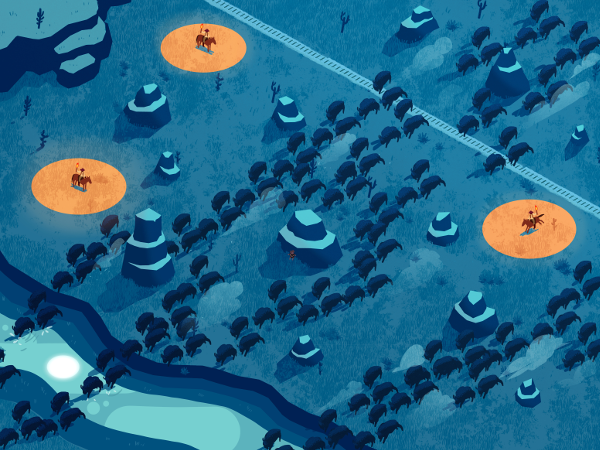

We wanted to create a very clear separation between light and shadow, between being seen and being hidden. The logic switches though, once you’re out in the desert and shadows are scarce: you need to find other ways to distract the bandits, buffalo, and coyotes of the environment.

EM: Given that gamers play as a child protagonist, how does that temper your inclusion of outlaws, shady saloons, and other staples of western storytelling? While the audience sees things from an isometric viewpoint, do you as developers create the world as viewed from a youth’s perspective? How does it change the game that we’re a six-year-old and not a cocky adolescent?

JS: Throughout the game you trigger little storylines that give a sense of childish innocence: from splashing through water although it’s loud and attracts opponents to being scared out of your hiding spot by a little mouse. These little storylines gradually intensify and become complete levels – at one point the boy falls into a barrel of wine and the game completely changes for a level, showing how his perceptions have changed.

El Hijo gradually evolves from an innocent child in search of his mother to a proactive, more mature character inspiring other children who have shared his fate. He eventually seeks revenge on the bandits who burned down his farm house.

EM: Game locations include a remote monastery, an unforgiving desert, and a dangerous frontier town, so how do you see one destination flowing into the next? In terms of user experience, what kind of flow (engagement, mechanics, etc) guides your levels?

JS: One of the first things we developed for the game was a level map, describing the journey of our character.

Starting from the tenth level of the monastery going down to the underground tombs, El Hijo manages to escape and come out into the desert through an empty grave.

Crossing the desert, he’s forced to go underground again through the mines, half-abandoned, half busy with desolate miners.

The exit of the mines leads him right into a dangerous shootout between bandits and lawmen. El Hijo has to hide but is accidentally picked up by a bandit and ends up right in the heart of the bandit camp from where he will need to escape, cross the desert, and jump on a train, which will bring him to the city. Bandits have his mother captured on the top of the saloon, and he now has to go up to save her.

EM: I’m interested in how Honig Studios projects like Impossible Bottles also contributed to your developer community; what do you see as milestones and benchmarks that have advanced your team, and when it comes to technical versus creative hurdles, what time sucks do you aim to mitigate in the future?

JS: The projects we develop usually take two years to produce, as our production method is very agile. We’re on the second year of El Hijo, and we’ll need one more year to get it done.

Although the technical side is a large chunk of the project, it’s usually the creative part that expands the time invested on a project. New, better ideas emerge while developing, testing, playing and it wouldn’t do the project justice if we didn’t add them into the project due to time restrictions.

Diving into two game projects in parallel was a challenge, but we feel very embraced and supported by the developer community in Berlin and worldwide.

EM: The spaghetti western constitutes a specific genre and place in Americana, a genre that comes with its own conventions, staples, and classics to draw upon. At its best, what kinds of stories and experiences do you see westerns providing, and how do you realize this within your work?

JS: We love the contrast that spaghetti westerns have: defenseless characters, trickery and deceit of opposing gangs, humor, and even surrealism. Putting a child in the central role means that we place less importance on violence and more importance on the environment and characters. We try to incorporate these elements in the storylines that unfold, and in other aspects of the game, too, drawing lots of inspiration from the genre.

EM: I see that stealth mechanics include throwing objects to create distractions, strategic hiding, use of shadows/light, etc; what other in-game options provide for varied gameplay, and where do you see a crossover between muscle memory and a creative use of the environment?

JS: The player can play through the game by using those basic mechanics of hiding and distracting. Additional layers to puzzles are gradually revealed, with moving and pushable objects like wagons that give you more options to find new ways to sneak around. Later in the game, you find your first weapon, a slingshot that enables you to both distract enemies and effect the environment in different ways. In the town, the slingshot can become a dangerous tool if you aim it at jars of nitroglycerin.

EM: As Honig Studios creates content for ‘games, film, TV, web and experimental channels’, I’m curious about how you see these mediums changing with regard to indie games. Have the dev tools of the last decade uncorked a fountain of creativity, or has the market become flooded with projects? How do you see TV and film, for example, changing in response to the huge online gaming markets, and what do you see constituting the next frontiers?

JS: Surely, developer tools like Unity and the open source community around those tools have enabled creatives to build projects with little technical knowledge. All media benefits from that. We strive to see what types of stories are suitable for which platform; some stories are better told in the cinema while others require more interaction and playful participation.

In case you missed it, here’s the teaser: