Interview: Dreamscaper Dev Team

A roguelite from Afterburner Studios, Dreamscaper invites players to unlock the power of sleep and deal with nightmares in levels that take a steep dive into the protagonist’s personal history. With deep combat and a journey through the shifting unconscious in mind, I chatted with the dev team (Ian Cofino, Robert Taylor, Paul Svoboda, Dale North) on the themes and ideas driving their work.

Erik Meyer: Dreamscaper delves into Cassidy’s unconscious as a RPG roguelite, so given the freedoms and conventions of the genre, how do you see the world you’re creating departing from convention, and as developers, how do you keep a dream setting from being too open-ended while maintaining consistency?

Ian Cofino: That’s a great question, and something we’re always going back and forth on.

We went with the dream fiction because we loved the possibilities that could be explored and the freedom it gave us. This, of course, is a double-edged sword. On one hand, there is a huge range of possibilities. On the other, we have to define how we interpret “dreaming” and what the rules of our world are. So we have to create our own constraints, because, as you mentioned, without that we lose consistency and the story; settings and gameplay will not feel grounded.

So far, we’ve created a “reality” where the dreams are less abstract and are pulled from reality so players can better understand who our main character is and what she’s going through. That will shift as the dreams get more surreal over the course of the game.

EM: Battles include real-time sparring with nightmares, incorporating melee, ranged, and dream powers, not to mention blocking, dodging, and parrying. As viewed from above, what kinds of strategies and tactics do you see setting apart this aspect of gamefeel from other powers-based game experiences? And what philosophy drives the kinds of play you’re aiming for?

IC: This is also one of the reasons that we’re really excited about our fiction. Dreams give such a wide variety of powers and possibilities.

With more conventional magic systems, there are more strict rules and limitations on powers. For us, one of the most exciting things about dreaming is that we can allow players to bend and warp reality in interesting ways.

This also allows us to draw on many sources of inspiration, so players are not limited to, let’s say, time period specific weaponry. Players can box, fire laser eyes, swing swords and rend the earth itself. We’re really trying to have a large and unique gamut of possibilities that will be fun for people to experiment with.

As of now, we have a variety of unique powers, like the ability to freeze the world and shatter enemies with a snap of your finger, or the ability to slow down time to get the upper hand in combat. Our plan is to continue to expand on them, making them even more outlandish and surreal as we continue.

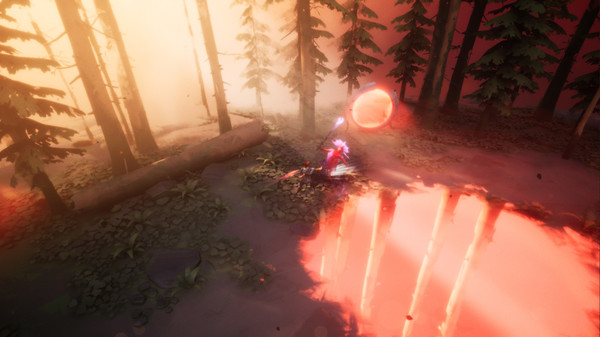

EM: Color and lighting brings the different levels to life in the teaser you’ve just released, and I appreciate snowy touches coupled with a bluish tint, much as the forest ferns and wooden-bridge gateways draw me in, respectively. When it comes to art assets and level design, what do you feel does the most to create organic scenarios and propel narration? What do you view as must-have props, and how, as a team, do you arrive on an aesthetic?

IC: Early on in the project, we discussed how we would tell our character’s story. We wanted to rely on visual storytelling in the world to do this. Small props bring life to scenes. Since they are things we interact with on a daily, human level, they become part of our life’s narrative, and have meanings attached to them, utilitarian or emotional, often both. We knew we would need to create a large amount of these props to adequately tell a story across multiple levels, and that they would have to be relatable, grounded in reality, and identifiable. Given our team size – all the environments and characters would be handled by one person – scope became a defining factor in choosing how we would build these props – they would need to be simple and easy to create.

We also thought a lot about dreams and how they felt to us – soft, hazy, half-forgotten. Impressionist paintings convey similar ideas, and we were drawn to the ‘half-finished’ nature of them – choosing to convey the interaction of light instead of representational detail, leaving the hand of the artist visible, receding the world into fog and light.

Although our tone is dramatically different, we also looked at the work of Beksinski. We were inspired by many of the elements that make his paintings so interesting – soft lighting, gradients of color with slight textural variation, shapes receding into a fog.

All these factors and influences eventually boiled down into a couple motifs which we used to define our aesthetic.

EM: I’m curious about your take on lucid dreaming, as Cassidy seems to exhibit a certain amount of freedom but clearly isn’t able to act with impunity. In the expansion of a person’s ability to alter experiences while asleep, I’ve found myself able to stop time, move instantly between life moments, and instantly create scenarios to my liking. To this end, how do you see ‘rules’ existing for Cassidy, and as devs, how do you see imposing oneself upon a mental construct reflected psychologically in said abilities?

IC: There are two sides to this. One stems from the question, “What do we want to communicate to players and how do we want them to interact with the world?” The other, as is often the case with game development is, “What can we achieve given our small team size?”

To your question, we initially started in a more restrained manner – we knew we wanted to create a rogue style game that has a heavy emphasis on ARPG combat. This, in and of itself, put some constraints on us. We knew we wanted players to be challenged and to grow better over time. This means that we can’t allow players too much power or control as there would be no challenge, which is so core to rogue-styled games.

In terms of the “what do we want to communicate to players” – we also want to tell a story that feels genuine to us, that deals with difficult issues and more serious topics, like loss and depression. This helped set the tone and allowed us to understand that in order to communicate themes and story properly to the player, we’d need to be somewhat restrictive on their ability to affect the world. The player’s struggle and lack of full agency as a lucid dreamer is reflective, for us, of the character’s own struggle and challenge in dealing with her own thoughts and emotions.

Finally, looking at it from a strictly rational, development perspective; our conceit that players have limited control, but strong powers and possibilities, aligns with what we can achieve as a three person team.

EM: Can you describe the game’s exploration elements and the ways in which players will stumble across backstory? While Cassidy has a huge bone to pick with the nightmares in her summer camp and home memories, it’s also compelling to know what literary tools you employ; with so many games that devolve into grinding, I’d love to hear about character development and the writerly elements at work.

IC: That’s our next big milestone to tackle actually.

The three of us really want to make sure that we treat our subject matter with respect. We’ve identified that a more minimalistic approach, that emphasizes subtext, will be appropriate for the story we want to tell, and how we want players to feel.

That being said, we’re trying out a few ways to approach this. There is a very large environmental story-telling component, as we know that players will be playing these levels over and over; we want their understandings of Cassidy and her situation to grow over time.

We’re currently working on tying the waking world to the dreaming world so we can flesh Cassidy out more as a person through the interactions players will have outside of the dream.

And more to your point about grinding – we plan on having a combination of persistent and linear story moments. We want players to feel rewarded for their progress outside of a single session – and that shouldn’t just come through gameplay upgrades; it also means expanding the player’s understanding of who they’re playing as and what her story is over time.

EM: While the current teaser has caught a lot of attention, Afterburner Studio has been hard at work for some time, so given your dev team’s small size, can you walk me through the creation of an area and what kinds of decisions go into your work? What kinds of happy accidents take place, how rigorous is your planning phase, and what kinds of things have gotten left on the cutting room floor?

IC: When we start out building a level, or dream, we brainstorm ideas for the types of stories we could tell in each dream. These ideas become the “story rooms”; hand-composed areas which guide the player through a moment in our character’s life. We create a number of these, which then become ‘themes’ (a “park”, a “commercial establishment”, a “residential area”) that define our combat spaces and give us props we can re-use to craft those areas.

The process is pretty organic, and the stories we tell can often change, morph into something else, or are fleshed out over time as we create more props and learn and discover new ways to build out areas.

EM: For me, dreams often exist as self-contained universes with their own internal logic; for example, I might dream that I’m 10 and aliens are invading and Scott Bakula is my father (he’s not, in real life). I don’t tend to question these details in the dream state, and odd elements frequently pop up without seeming strange. I accept bizarre moments and journey on. For your team, what kinds of inclusions feel ‘too dreamy’, and how do you balance that against ‘not dreamy enough’?

IC: Sure, who hasn’t dreamed that Scott Bakula is their father and also they’re future vampires fighting zombies in the past?

That’s a constant balancing act for us. We’ve started with a more grounded dreamworld, which has given us the space to continually layer in more and more surreal elements.

In general, we’ve identified that to achieve that surreal, semi-bizarre state that you’ve mentioned, you also need to have things that anchor you to the space. If everything is surreal and random, nothing is surreal. In order to actually create a dream-like quality to the game, we want to make sure that players have a point of comparison so that when we push things really far, there’s true juxtaposition between that and the more grounded elements.

EM: I experience memorable dreams as a blending of nostalgia and high emotion, often paired with fantastic details. I might join forces with my grandfather and do battle with grocery store managers in a greenhouse, armed only with rear-loading penny guns. Following painful defeat, I might wake up to a pillow of tears. What do you see as the trickiest part of translating a sleep-life into a digital experience? And to this end, the compelling, player-engrossing end, where do you see yourselves on your journey? What milestones have you already achieved, and what hurdles do you anticipate in the near future?

IC: One of the most challenging elements of translating dreams is that they’re so personal. Everyone perceives things differently and there isn’t necessarily a “right” answer to what constitutes a dream. We had to take time to define what dreaming was in the context of our game, for our character, Cassidy.

We feel like we’ve made really fantastic progress on some of the core elements that make up Dreamscaper – combat, exploration, rogue-styled mechanics. Our next big milestone will be tying dreaming and reality more closely to one another. We have some creative and technical hurdles ahead, but we’re excited to create an experience for players that will feel personal, heartfelt, and most of all, fun.

In case you missed it, here’s the trailer: