Interview: Born Punk’s Falko von Falkner

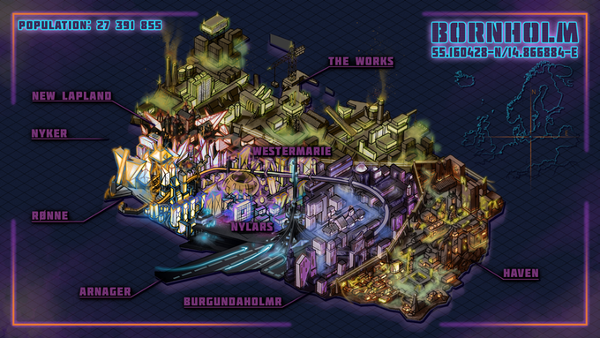

Born Punk drops players into a point-and-click cyberpunk sci-fi adventure, drawing its pixel art style from ’90s classics. Following Eevi, a former corporate hacker infected by a rogue AI, the narrative begins with a return to humble beginnings and evolves into a conspiracy across the Danish island of Bornholm. I chatted with Insert Disk 22 founder Falko von Falkner on the finer points of his work, noting the specifics of the created universe and the larger project goals.

Erik Meyer: Born Punk is set within a cyberpunk backdrop, so I’m interested in the rules of this specific cyberpunk society. How would you describe the relative technology levels, in terms of current technologies, emergent technologies, and disruptive technologies, as opposed to the world we currently live in? What other kinds of social and environmental factors should players expect?

Falko von Falkner: I tried to come up with a relatively realistic progression of technology. I think most sci-fi and sci-fi-like franchises are a bit too optimistic about our trajectory. Look at Star Trek, for example; if we don’t invent some kind of miracle technology soonish, it is extremely unlikely that we’d have a multi-star-system-spanning star empire within the next 200 years. In Born Punk, technological progress was driven by commercial demands. As our resources on Earth declined, corporations started to build outposts in space. Throughout history, there is a clear correlation between progress and necessity. On the other hand, I’m painting a more optimistic picture about our environment than is expected in cyberpunk, or even our real life society. As I do believe that when catastrophes become imminent, humanity is quite capable of working together, in the world of Born Punk, most environmental issues have either been resolved or are in the process of being resolved. Within our setting, Brazil even became one of the most powerful countries on Earth by focusing on innovations in ‘atmosphere scrubbers’, giant factories that remove pollutants from the air.

Socially, the game is very much traditionally cyberpunky. Evil corporations everywhere, governments that are nothing but paper tigers, oppression of the working class – most of the cliches of the genre are present in Born Punk. And why wouldn’t they be! I do see our society willingly giving up self-determination in favor of giant soulless corporations. Google and Facebook dictate what can and can not be said online, and people cheer them on. As long as these corporations pretend to align with a person’s personal worldview, people are quite willing to give them power they should never have. Due to this observation, I found it unnecessary to deviate from cyberpunk’s formula in this regard.

EM: From the emergence of visual gaming in ’80s, point-and-click adventures have existed as a distinct genre, so within that context, what do you see as must-do elements that determine the success and engagement of point-and-click titles? Given the less immediate perspective (as opposed to fast-paced first-person shooters), what expectations do you coming from the player audience?

FvF: I don’t think there is a must-do within the genre. Wadjet Eye games like Unavowed play completely differently than Telltale Games. Daedalic’s Deponia series is a completely different kind of beast than Myst. At its core, ‘point and click’ merely describes a very basic game mechanic. What unites all these games is a love for story, and perhaps a more relaxed approach to game design; twitch skills and time limits are rarely if ever seen within the genre. I’d claim that the appeal of point and clicks is to be able to immerse yourself in a fictional world at your own pace. It’s the gaming equivalent of a wine tasting, rather than a beer binge. Nothing against beer, though.

EM: Born Punk includes lore as part of the exploration, revealing knowledge (if the player looks for it) that leads to different in-game outcomes; as a player who loves world creation and backstory, I tend to eat up lore, so what led to this mechanic for encouraging exploration and information gathering?

FvF: That’s just me being me, a contrarian. The modern principle of storytelling in gaming is very much ‘show, don’t tell’. I would like to prove that there is very much room for ‘tell’ as well, and which genre is better suited for that then the already slow, sombre point and click one? I can see how reading through a wall of text might ruin the pacing of a first person shooter, but it doesn’t seem very distracting in a game in which passively listening to dialogue is a very common element. Yes, there will be times in the game in which having sought out lore entries will be beneficial to the player, in which knowing lore will advance the story in a certain way. But not knowing that lore will never lead to a game over or a fail state, therefore, I hope that even those who don’t care about lore all that much will be fine with its inclusion.

EM: As a fan of pixel art and the sustained emergence of retro gaming over the last decade, I’m curious about your guidelines and process when it comes to the game’s visual look. Art can be a tricky thing, in that what looks good and what feels a bit off can be fairly similar; in everything from color palette to game menus, is this more of a leave-it-to-the-graphic-designer thing, or do you blend prototyping and narrative work as a team, or do you have a different process entirely?

FvF: Personally, I’m not a fan of the term ‘retro’ when it comes to pixel art. One reason for that may be because I’m an old fart and the 80s just happened like two years ago in my head, but the other reason is that calling pixel art ‘retro’ seems kind of unintentionally demeaning. Let’s compare this to paintings: certain painting techniques were developed hundreds of years ago and are still used in modern art; these don’t get called retro, they get called by their name. Pixel art is an art form, just like realism is, just like expressionism is, or to stay with computer games, just like photorealistic graphics are. Having said that, I’m a complete ignoramus when it comes to the intricacies of the technique. This is why I hired Indrek, our graphics artist. He has complete and utter freedom when it comes to designing our scenes, characters and animations. I just tell him my storytelling and puzzle vision for each scene, sketch a horrible looking drawing thing, and then he mixes his graphical vision with mine. So far, this has worked out really well. Very often, his graphical vision has even made me change the story, or a puzzle, because he added elements to a scene that I didn’t expect or ask for. Our creative process is definitely a two-way street.

EM: The three characters – a former hacker, a CEO, and an android obsessed with 80s culture – frame narration from three distinct vantage points, so from a literary perspective, did you create the characters and let them guide the story, or did you create a detailed plot that allows these characters to shine (or a mixture of the two)?

FvF: I only have a few ‘hard milestones’ in my head, that NEED to happen. The story development inbetween is fluid and subject to constant change. Generally speaking, the characters serve the story, and not the other way around. Of course, all three characters have strong and very distinct personalities that won’t change just to advance the plot, and all three characters will have very personal moments in the game, but the overarching story is boss. Interestingly enough, I have noticed that as we move from one chapter to another, roles that I thought would fit one character perfectly actually end up being given to another character. I’m also noticing that whilst at the beginning of the project, Eevi was definitely the main protagonist, Mariposa (our corporate CEO) and Grandmaster Flashdrive (our Android) get more screen time than I thought they would. This happens because as I get to know our own characters better, more opportunities to utilize them pop up in my head.

EM: I’d love a bit of backstory on Insert Disk 22; as someone who remembers a time in the ’80s and ’90s when games came in cardboard boxes with a pack of floppy disks, the name feels nostalgic, a nod to a different time. As a studio, what does your current process of creating content look like? How do you approach goal setting and milestones, and how do you mesh the best aspects of retro with the tools of today?

FvF: The game is definitely a nod to a different time, and I’m not ashamed to admit that it is designed to play like a game from the 90s. The modern gaming industry has perfected streamlining, minimal UIs, sleek storytelling, and efficiency. But with those changes, many games began to feel soulless. Too… designed, perhaps. Too… deliberate. I’m trying to capture what I perceive to be the soul of these old games, and to move ID22 forward in our own little time bubble. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that, and capitalistically speaking, I also think there’s a sizeable amount of people who think in a similar way. As to our internal processes, in THAT regard we’re pretty laissez faire and modern. All team members are quite independent personalities, so apart from me saying ‘We need to be finished with X by X’, the team members decide on their own how they spend their time, and how much time they spend. I care about good results, not that somebody clocks in or out at a certain time. So far, it’s been working out really great, as we’re all able to self-motivate. We communicate exclusively via our discord server, and that’s pretty much it!

EM: One thing I have a hard time putting my finger on is why games like Monkey Island or Day of the Tentacle somehow evoke more mystery and feel, in their cartoony ways – coming across as more genuine – than many of the 3d games with higher production values that have emerged in the decades since. When it comes to the gravity of an experience, what do you see happening in point-and-click adventures that creates such gravitas?

FvF: I think this relates to my point about the ‘soul’ of these games. If I had to put my finger on it, a game’s soul is defined by the love poured into it, not its coding techniques or engines or technical fidelity. ‘Core gamers’, for a lack of a better term, notice if a game is mostly a commercial venture or whether it’s a project done out of love. The former refuses to offend, to take risks, to make something just because a designer thought it would be cool or fun or interesting. The latter on the other hand WILL offend, WILL take risks, and WILL put in cool things just for the heck of it, even if it may not be the most rational commercial choice. The usual comicy graphics style of point and click adventures certainly helps, too. A photo-realistic Guybrush Threepwood would never be able to solicit the same emotions as a comic Guybrush Threepwood can. The comic style gives him some sort of innocence and cuteness. It also helps that comic style games tend to age better than games that try to keep up with the latest graphics trend! State of the art graphics will eventually always look dated.

EM: You ran a successful Kickstarter campaign, so as a form of debriefing, I’m curious about that experience. When it comes to the balance between releasing content, reaching a larger audience, using social media, and engaging media during a crowdfunding effort, what kinds of things made the most difference, where did frustrations emerge, and where were you pleasantly surprised?

FvF: I had an audience on both YouTube and Twitch, so that definitely helped the most. I didn’t have to start from zero. Then, I spent a lot of time cultivating relations with games journalists; and I don’t mean in the insincere ‘networking’ sense. Networking is just another term for ‘pretending to like someone so they will eventually do something for me’. I mean actually engaging with them, without ever pretending that I DON’T want exposure. They’re professionals, they know what’s up. In a professional environment, there’s no need for feel good pretense. So yeah, we got a lot of coverage for our Kickstarter from places I didn’t expect. Like Germany’s two biggest games magazines, PC Games and Gamestar. My own community, most importantly my twitch community, also helped tremendously. These buggers are so dedicated and shared the word so much and so often that even I started thinking ‘isn’t that a bit much… heh’. I’m very grateful! As to frustrations, to once more stay honest: we were hugely trending on Kickstarter at points, but weren’t promoted on their frontpage. Boo. Boooo. 😉

In case you missed it, here’s the gameplay demo: