Interview: Boot Hill Bounties’ David Welch

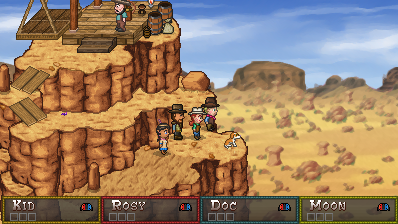

The second in the series by Experimental Gamer Studios, Wild West JRPG Boot Hill Bounties pits players against five legendary outlaws in a SNES-era-inspired pixel art experience. Featuring up to four player local co-op in addition to single player, the game pleases crowds and individuals equally, and I chatted with dev David Welch on the thought process behind the project.

Erik Meyer: Drawing on the tradition of Final Fantasy, Earthbound, and Chrono Trigger, Boot Hill Bounties takes classic JRPG stylings to the wild west; in terms of setting, what has drawn you to the lawless frontier of yesteryear, and beyond basic in-game mechanics, how do you see the games that inspired you finding their way into your work?

David Welch: The idea behind choosing a Wild West setting was realizing traditional JRPG tropes in a unique, non-fantasy environment. So for example, dragons become bears, airships become trains, legendary swords become legendary guns, powerful wizards become powerful desperadoes, evil chancellors become evil business tycoons. I’m sure people will notice the visual inspiration from those traditional RPGs, but there’s also inspiration in story pacing, tone, and scope.

EM: BHB has a number of things for players to engage with, including newspaper side quests, farm-related upgrades, recipe power-ups, and weapon mods. Can you walk me through a ‘how’s that going to work’ and a ‘how’s that going to work with everything else going on in the game’ scenario for adding a system that adds or expands on play options?

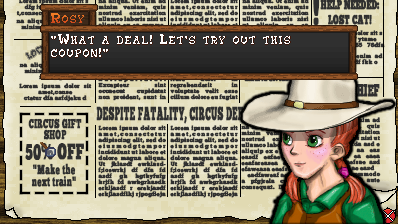

DW: That’s a good question because you don’t want players to feel overwhelmed with too much side activity and interruptions. So most of it is organized and relegated to newspapers and campsites.

The story has five distinct chapters, and after the end of each chapter, a new issue of the Bronco County Sunrise newspaper is released. Among other things like current events, obituaries, advertisements, recipes and coupons, the newspaper points to every new side quest that opens up. By releasing the newspaper after each chapter, it’s the perfect opportunity to take a break from the main storyline and explore the world with some of these side quests before embarking on the next chapter (of course you can always come back and finish any of the side quests at any time). So you’re not interrupted while in the middle of a chapter. The newspaper also helps you keep track of which side quests exist and which you have completed. So you don’t have to run around Bronco County hoping to unlock these events somehow. It keeps things organized and focused.

The campsites also serve as a small break from the story where you can focus on some side activities. During your adventure you’re often picking up reagents for weapon modifications, ingredients for cooking, and wounds for treatment.

When you camp, you take a break from the adventure and can put all these acquired things to use.

EM: The pixel art style certainly reminds me of classic SNES titles, although battle strikes me as a nod to Phantasy Star III with the first-person view of enemies; as you’ve included different art elements, what take-aways and ah-ha moments have you had in the areas of look-feel, gameplay, and transitions between different elements?

DW: Yes, the first person battle view is a pretty classic view for combat. We chose this because we wanted the combat to have a ‘shooting gallery’ feel. That’s why the enemies often look like flat, wooden targets which wobble back and forth when hit. And this shift to a shooting gallery also helps emphasize that the gameplay in a battle is not a literal account of what is happening in the story. I think traditional RPG fans have come to accept that, but we wanted to make it extra clear.

One ‘ah-hah’ moment is that in one battle, the wobbling and of the wooden cutouts actually becomes a gameplay element and not just an aesthetic effect. I won’t point out exactly how that works here as I want it to be a surprise.

EM: This isn’t your first game, and as a sequel to Boot Hill Heroes, what have you both taken from that experience and moved away from as you’ve worked on BHB? In terms of your community, what kinds of things have they asked for?

DW: I’m sure it’s true for most creators that the more time passes after you create something, the more room you see for improvement. So Boot Hill Bounties was a chance to improve on a lot of ideas in Boot Hill Heroes, which is probably also why it took so long to develop. For example, the art was almost completely redone.

As far as community feedback, one thing that some people weren’t crazy about in BHH was the fact that it’s a four player game, but you don’t acquire all four characters until late in the game. Since this is a follow up, the characters have already met. So the only reason not to have the game start with all the characters is to not overwhelm the player. In Boot Hill Bounties, you begin with one character, but acquire the rest, one by one, in the first 10 or so minutes.

EM: To put it simply, the history of westward expansion across North America and the near-constant wars (and war crimes) perpetuated by the U.S. federal government is nothing short of monstrous. While the game fictionalizes the past, how do you touch on this difficult aspect of the time period while not having the resulting heaviness affect the experience in a negative way? To my view, gamers appreciate honesty and clarity, so how do you address things (in writing and scenes) while not having that take over the game?

DW: There’s no reason to avoid heaviness, that’s what makes stories interesting, after all. One way this game does diverge with a lot of traditional JRPGs is that the villains are not supernatural forces, they are people. In fact, probably half of the battles in the game are against human enemies. So there are a lot of conflicts over differing beliefs, perceptions or misunderstandings.

But I think one way that helps alleviate difficult topics is one afforded by this media. In RPGs, you get to meet lots of different people with a lot of different views and opinions. So it’s not just one point of view. I think that’s a really interesting way to explore heavy topics.

EM: I’d love a peek into your development environment, so can you describe your setup (hardware, software, engine) and the process by which you create assets, along with level and quest creation? What tools have sped things up for you over the last few years? What couldn’t you do without?

DW: Well, our engine is made from scratch and while it is very messy, it’s very easy at this point to create and add content. Almost too easy, as it has become hard to avoid scope creep! We don’t really use any other software outside the IDE other than Photoshop for the assets.

EM: Experimental Gamer Studios represents a small team based out of Chicago; as a fellow Midwesterner, what kinds of things from your American experience have been finding their way into your work? And in these strange times we live in, how far do you feel we are from the lawlessness of the wild west?

DW: One thing about the lawlessness of the Wild West is that people more often had to rely upon each other, neighbors and strangers, for help in difficult times. I think given the situation we are in now, we will start seeing more and more of that.

As a Midwesterner, I grew up in a small town, and I think small towns are sort of the heartbeat of the classic JRPG experience. So it was fun to give each town a distinct vibe and character.

EM: Your work takes on a number of understandable themes – gunslinging outlaws, brave lawmen, untamed wilderness – as you’ve gone along, how have you seen those themes bled together or become more complex? Certainly, the spaghetti westerns of the ’50s had a lot of stock characters (hero wears a white hat, villain wears a black hat), but telling stories in games is not unlike telling stories in novels, in that the author lives and breathes the characters. Without giving any spoilers, what types of character depth have cropped up in the project that’ve surprised you?

DW: I think the strongest part of Boot Hill Bounties are the ‘bounties’ themselves, the villains. So a lot of time is spent on getting to know these villains, each with different motivations and beliefs. So thinking about things from their point of view was often interesting and surprising. I don’t think any of them are the kind of villains who think they are doing good; they’re all pretty bad, and they know it. But they still have their own reasons for why they do the things they do.

For example, there’s one character that is really not much more than a thief. But when I started to think about why this character does this and how they see the world, it turned a pretty simplistic character into something I thought was very interesting. Having each chapter sort of dedicated to each villain was a fun opportunity to really explore them.

In case you missed it, here’s the trailer: